InfiniCache: Distributed Cache on Top of AWS Lambda (paper review)

“InfiniCache: Exploiting Ephemeral Serverless Functions to Build a Cost-Effective Memory Cache” by Ao Wang, et al. (link) is a recently published paper which describes a prototype of a serverless distributed caching system sitting atop AWS Lambda.

Most distributed caching solutions run on a cluster of VMs. The cost of such a cluster is mostly fixed and depends on required memory allocation, no matter how many requests it serves. InfiniCache aims to bring a serverless pay-per-request dynamic pricing model to the world of in-memory data caching.

While reading through the paper, I got fascinated by several techniques that they employed while implementing the system. Therefore, I decided to review the paper and highlight its most intriguing parts. I target my review at software and IT engineers working on cloud applications. I assume the reader has a basic understanding of serverless cloud functions (Function-as-a-Service, FaaS) and their traditional use cases.

Let’s start with a problem that InfiniCache aims to solve.

I. State in Stateless Functions

Serverless functions excel at running stateless workloads. FaaS services use ephemeral compute instances to grow and shrink the capacity to adjust to a variable request rate. New virtual machines or containers are assigned and recycled by the cloud provider at arbitrary moments.

Functions are incredibly compelling for low-load usage scenarios, among others. Executions are charged per actual duration, at 100 ms granularity. If your application only needs to run several times per day in a test environment, it costs you very close to zero.

Cloud providers try to reuse compute instances for multiple subsequent requests. The price of bootstrapping new instances is too high to pay for every request. A warm instance would keep pre-loaded files in memory between requests to minimize the overhead and cold start duration. The exact behavior is a black box and varies between region, AZ, and in time.

There seems to be a fundamental opportunity to exploit the keep-warm behavior further. Each function instance has up to several gigabytes of memory, while our executable cache might only consume several megabytes. Can we use this memory to persist useful state?

In-memory Cache

The most straightforward way to use this capacity is to store reusable data between requests. If we need a piece of data from external storage, and that same piece is needed again and again, we could store it after the first load in a global in-memory hashmap. Think of a simple read-through cache backed by an external persistent data store.

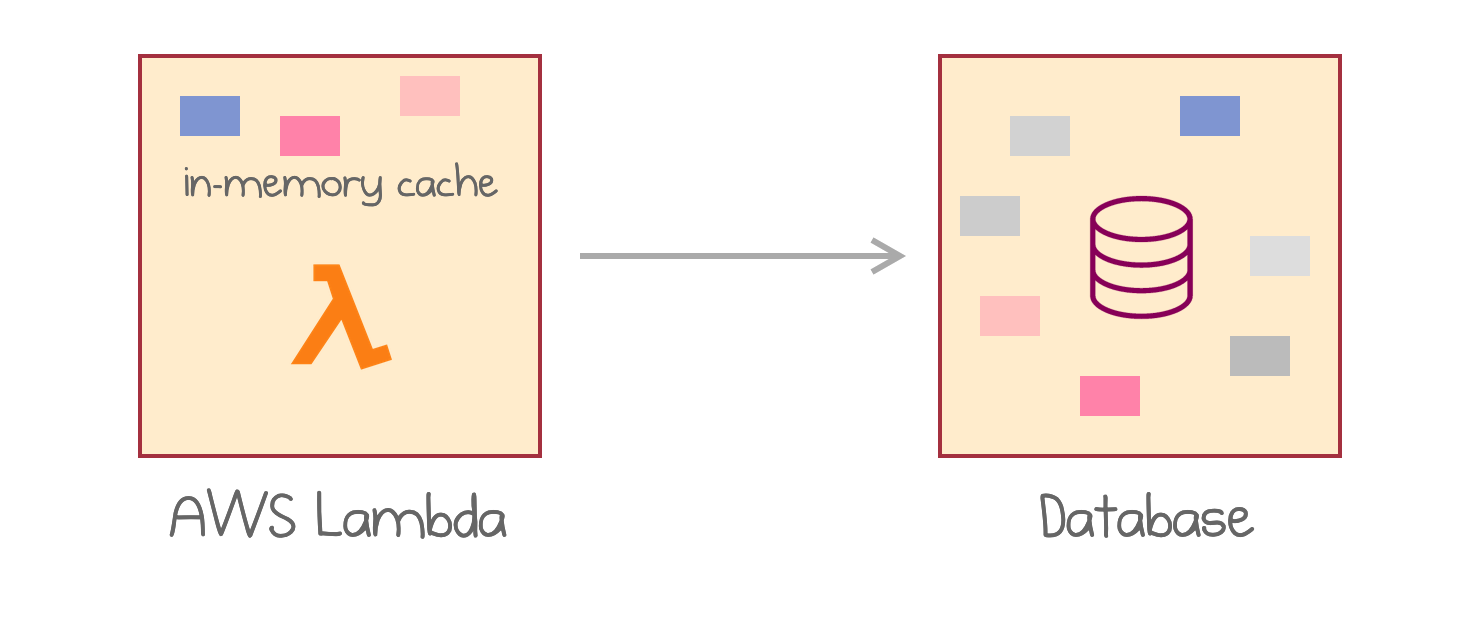

In-memory cache in AWS Lambda in front of a persistent database

This approach is still quite limited in several ways:

- The total size of the cache is up to 3GB (max size of AWS Lambda), which might not be enough for a large number of objects or large objects.

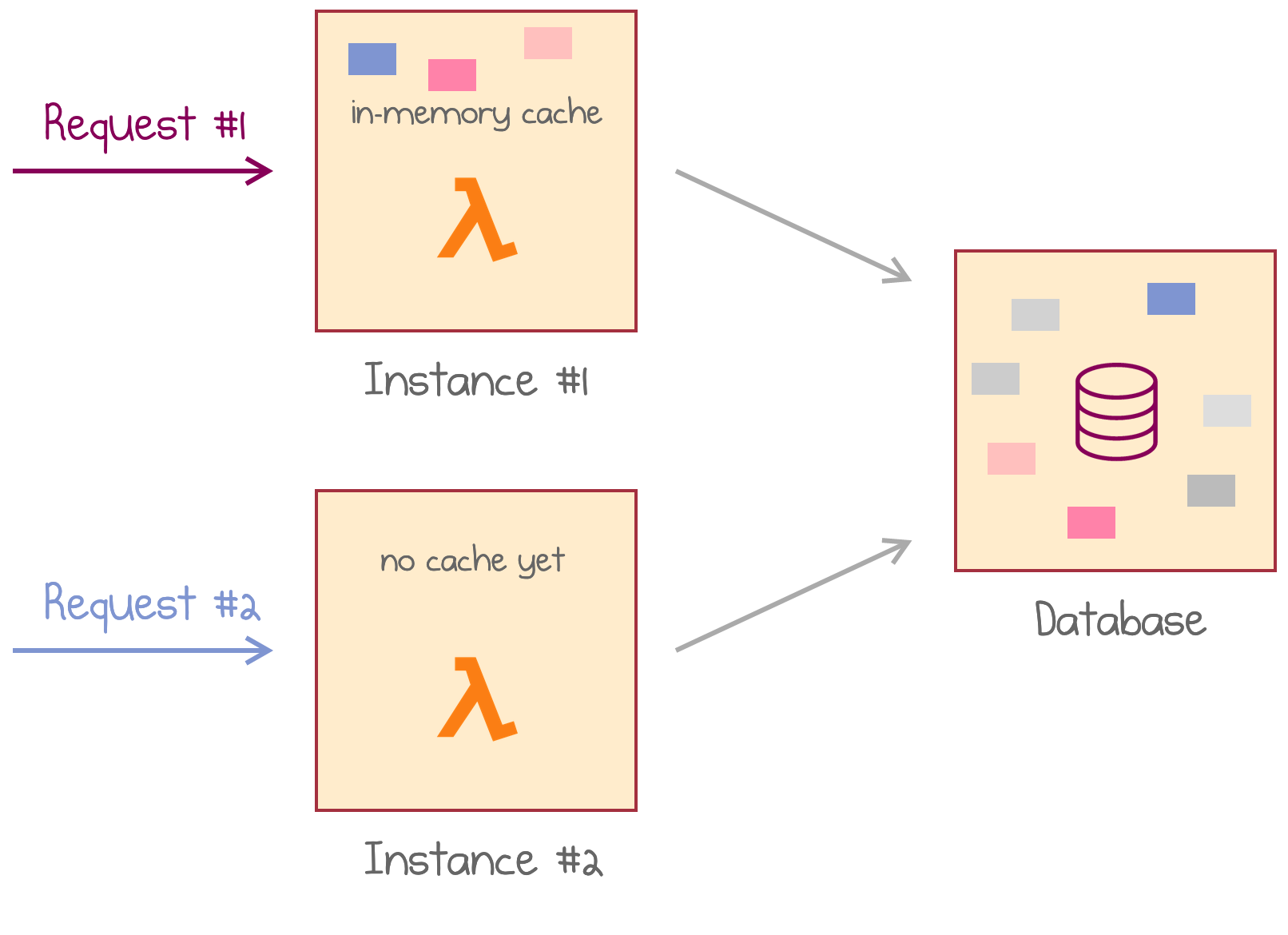

- Any parallel request hits a different instance of the same AWS Lambda. The second instance then has to load the data from the data store once again.

A parallel request hits the second instance with no cache available

Each instance has to store its copy of cached data, which reduces the overall efficiency. Also, cache invalidation might get tricky in this case, particularly because each instance has its own, highly unpredictable lifetime.

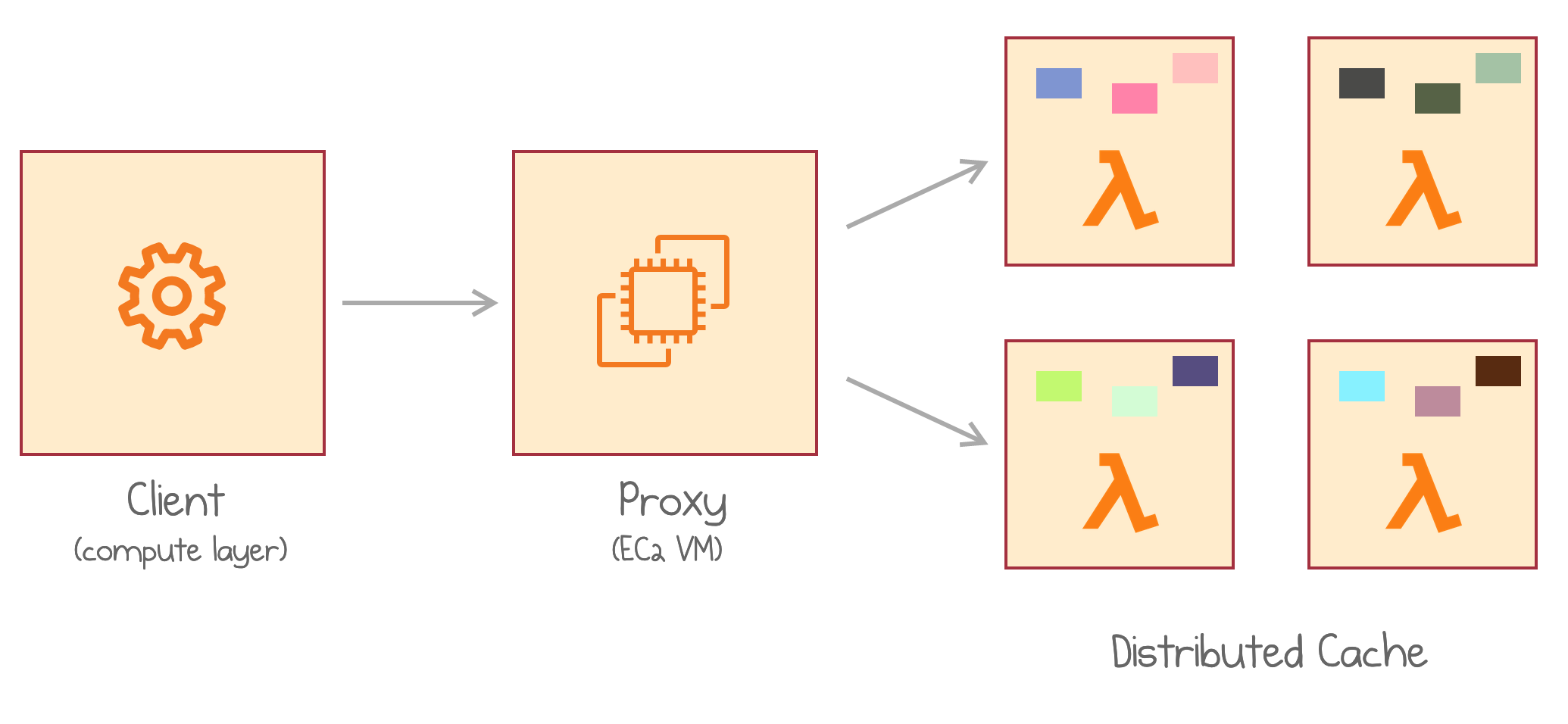

Distributed Cache

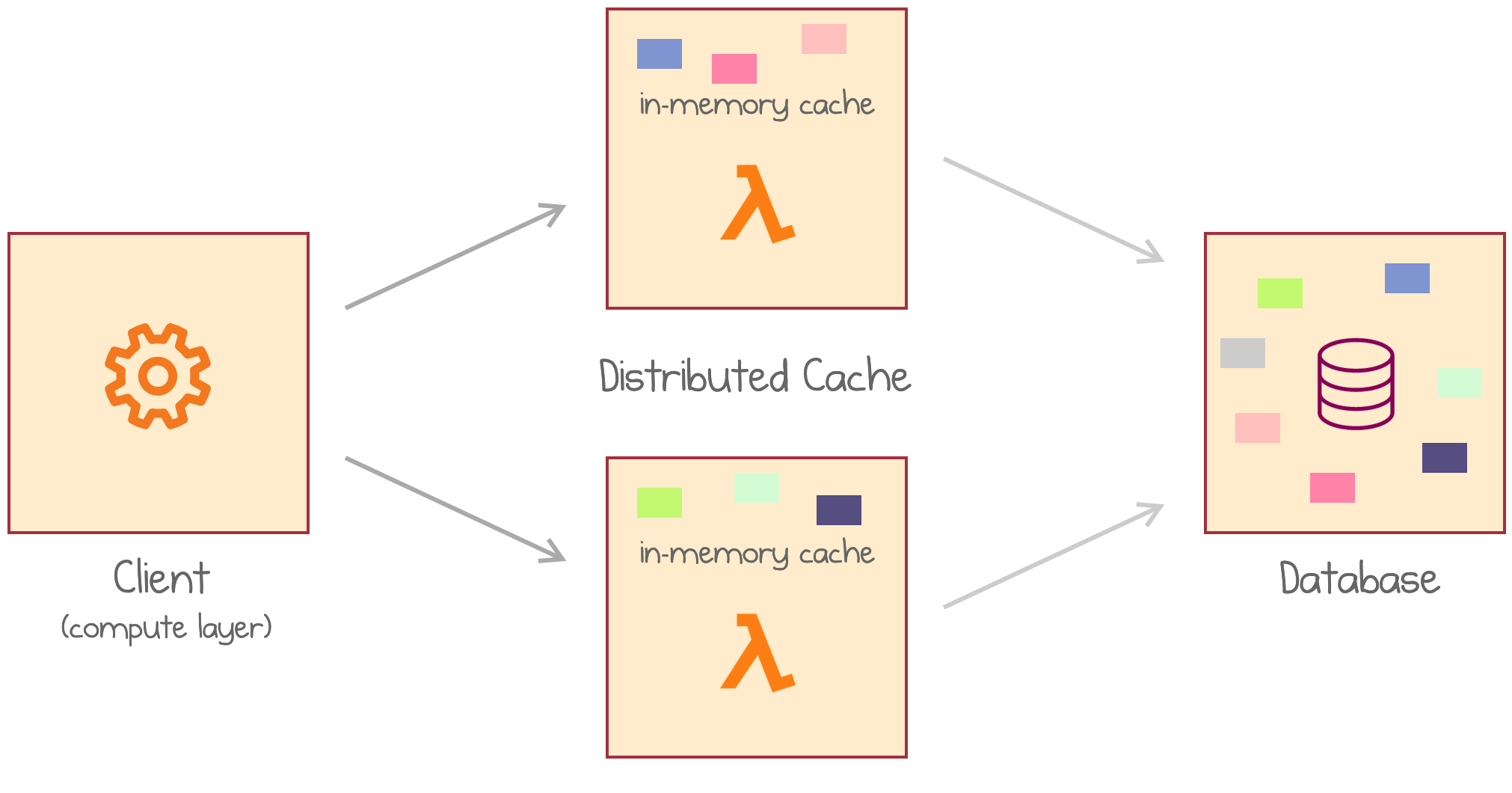

The previous scenario described a local cache co-located with data processing logic. Can we move the cache out of the currently invoked instance, distribute it among many other instances, and have multiple lambdas caching different portions of the data set? This move would help both with the cache size and duplication issues.

Application loads data from a distributed cache of multiple AWS Lambdas

The idea is to create a Distributed Cache as a Service, with design goals inspired by the serverless mindset:

- Low management overhead

- Scalability to hundreds or thousands of nodes

- Pay per request

The most significant potential upside is related to the cost structure. The cache capacity is billed only when a request needs an object. Such a pay-per-request model significantly differentiates against conventional cluster-based cache services, which typically charge for memory capacity on an hourly basis whether the cached objects are accessed or not.

Challenges

However, once again, serverless functions were not designed for stateful use cases. Utilizing the memory of cloud functions for object caching introduces non-trivial challenges due to the limitations and constraints of serverless computing platforms. The following list is specific to AWS Lambda, but other providers have very similar setups.

- Limited resource capacity is available: 1 or 2 CPU, up to several GB of memory, and limited network bandwidth.

- Providers may reclaim a function and its memory at any time, creating a risk of loss of the cached data.

- Each Lambda execution can run at most 900 seconds (15 minutes).

- Strict network communication constraints are in place: Lambda only allows outbound network connections, meaning a Lambda function cannot be used to implement a server.

- The lack of quality-of-service control. As a result, functions suffer from straggler issues, when response duration distributions have long tails.

- Lambda functions run at EC2 Virtual Machines (VMs), where a single VM can host one or more functions. AWS provisions functions on the smallest possible number of VMs, which could cause severe network bandwidth contention for multiple network-intensive Lambda functions on the same host VM.

- Executions are billed per 100 ms, even if a request only takes 5 or 10 ms.

- No concurrent invocations are allowed, so the same instance can’t handle multiple requests at the same time.

- There is a non-trivial invocation latency on top of any response processing time.

Honestly, that’s an extensive list of pitfalls. Nonetheless, InfiniCache presents a careful combination of choosing the best use case, working around some issues, and hacking straight through the others.

Large Object Caching

Traditional distributed cache products aren’t great when it comes to caching large objects (megabytes):

- Large objects are accessed less often while consuming vast space in RAM.

- They occupy memory and cause evictions of many small objects that might be reused shortly, thus hurting performance.

- Requests to large objects consume significant network bandwidth, which may inevitably affect the latencies of small objects.

Because of these reasons, it’s common not to cache large objects and retrieve them from the backing storage like S3 directly.

What is missing is a truly elastic cloud storage service model that charges tenants in a request-driven mode instead of per capacity usage, which the emerging serverless computing naturally enables.

II. InfiniCache

The paper InfiniCache: Exploiting Ephemeral Serverless Functions to Build a Cost-Effective Memory Cache presents a prototype of a distributed cache service running on top of AWS Lambda. The service is aimed specifically at large object caching. It deploys a large fleet of Lambda functions, where each Lambda stores a slice of the total data pool.

InfiniCache offers a virtually infinite (yet cheap) short-term capacity, which is advantageous for large object caching, since the tenants can invoke many cloud functions but have the provider pay the cost of function caching.

The authors employ several smart techniques to work around the limitations that I described above and make the system performant and cost-efficient.

Multiple Lambda functions

InfiniCache creates multiple AWS Lambdas, as opposed to multiple instances of the same Lambda. Each Lambda effectively runs on a single instance (container) that holds a slice of data. A second instance may be used for backups as explained below.

Therefore, there is no dynamic scaling: the cache cluster is pre-provisioned to the level of required capacity. This does not incur a high fixed cost, though: each Lambda is still charged per invocation, not for the number of Lambda services or deployments.

AWS Lambdas as cache storage units

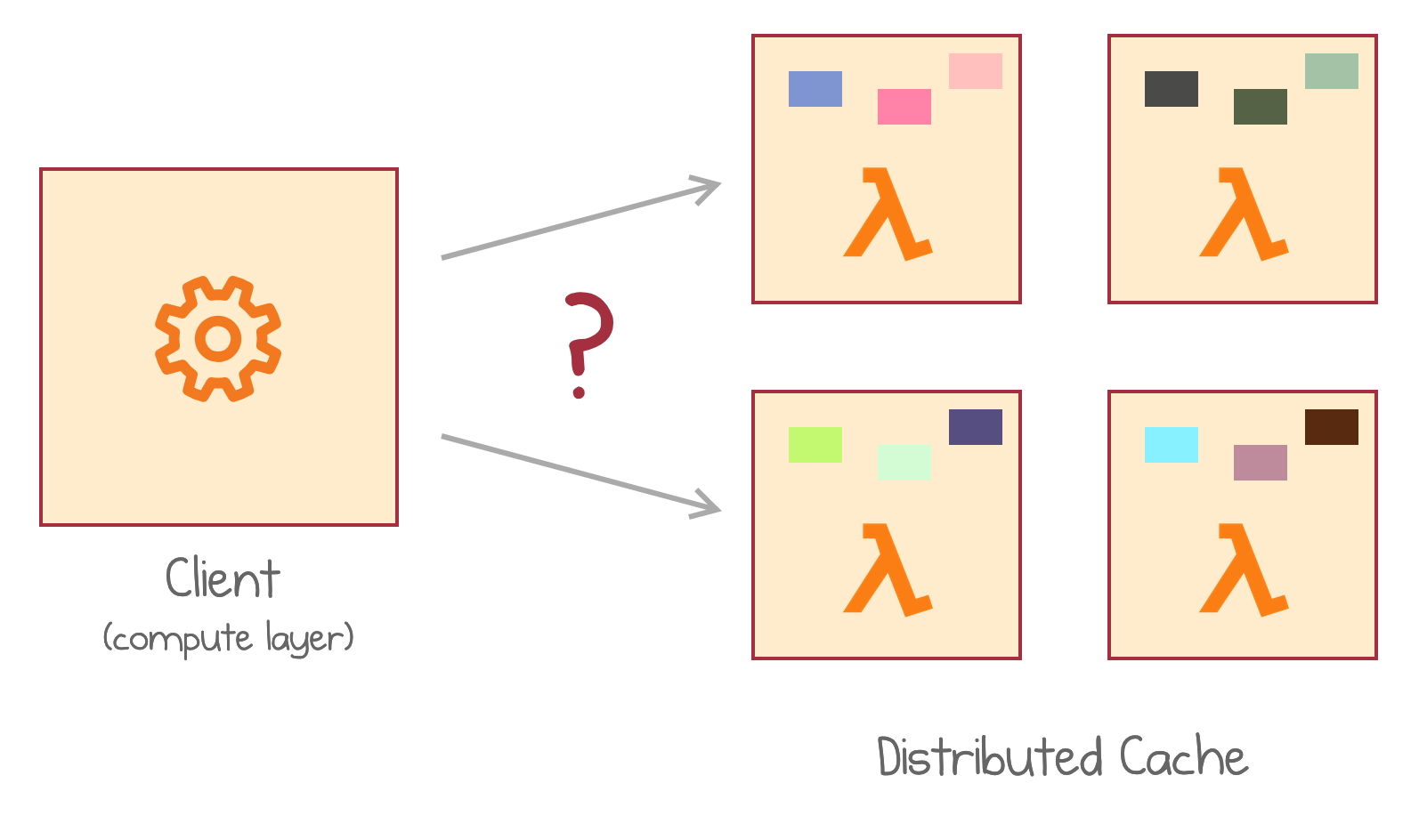

The described approach may sound very limiting. A single instance? Well, each instance can only handle a single request at a time, do the clients need to coordinate and wait for each other? How do the clients even know which Lambda to invoke to retrieve a piece of data?

That’s why InfiniCache has an extra component called a proxy.

Proxy

A proxy is a static always-up well-known component deployed on a large EC2 virtual machine. A proxy has a stable endpoint and becomes the entry point for all end clients. It then talks to Lambdas via an internal protocol, as I explain below.

A client makes requests to the proxy which connects to a Lambda

It’s now the responsibility of the proxy to distribute blobs between Lambdas and persist their addresses between the requests.

There may be multiple proxies for large deployments. InfiniCache’s client library determines the destination proxy (and therefore its backing Lambda pool) by using a consistent hashing-based load balancing approach.

On the other side, for smaller deployments, the proxy could be placed directly on the client machine to save cost and an extra network hop.

Backward Connections

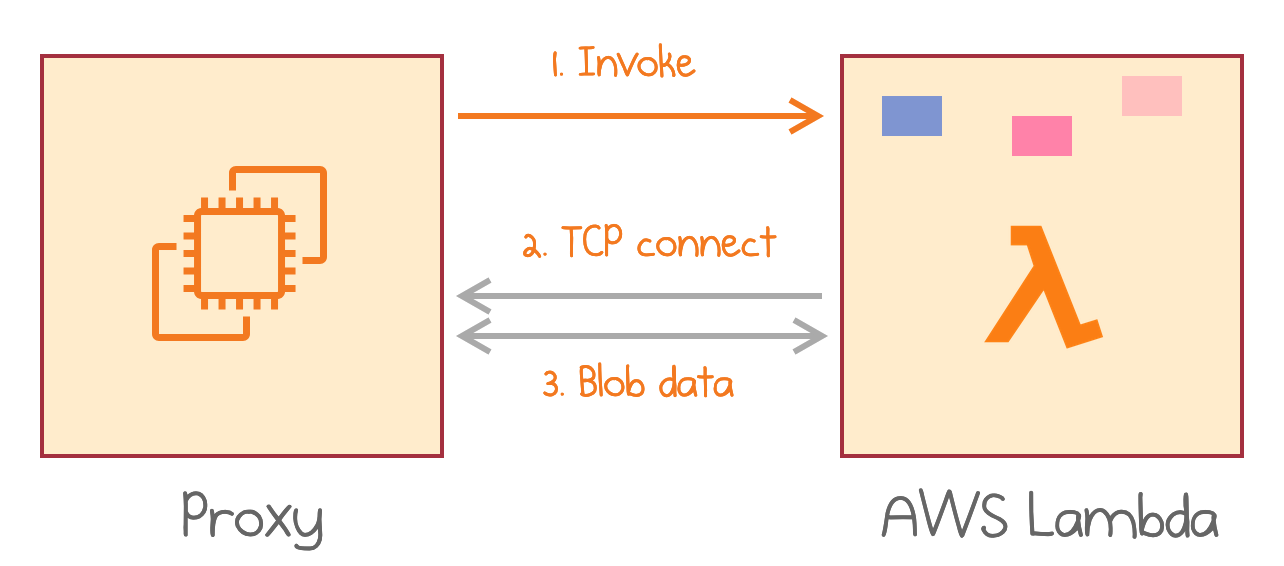

Firing a new Lambda invocation for each cache request proves to be inefficient: You pay for the minimum of 100 ms and block the entire instance for the single execution. Therefore, InfiniCache authors use a sophisticated hand-crafted model with two channels for proxy-to-lambda communication.

Traditional Lambda invocations are used only for activation and billed duration control. The same invocation is potentially reused to serve multiple cache requests via a separate TCP channel.

Since AWS Lambda does not allow inbound TCP or UDP connections, each Lambda runtime establishes a TCP connection with its designated proxy server the first time it is invoked. A Lambda node gets its proxy’s connection information via the invocation parameters. The Lambda runtime then keeps the TCP connection established until reclaimed by the provider.

During an active invocation, Lambda establishes a TCP connection for multiplexed data transfer

Here is a somewhat simplified explanation of the protocol:

- At first, there is no active invocation of a given Lambda.

- Whenever the proxy needs to retrieve a blob from a Lambda, it invokes the Lambda with a “Ping” message, passing the IP of the proxy in the request body.

- The Lambda invocation is now activated, but it does NOT return yet. Instead, it establishes a TCP connection to the proxy IP and sends a “Pong” message over that second channel.

- The proxy accepts the TCP connection. Now it can send requests for blob data over that connection. It sends the first request immediately.

- The Lambda instance now serves multiple requests on the same TCP connection.

- Every billing cycle, the Lambda instance decides whether to keep the invocation alive and keep serving requests over TCP, or to terminate the invocation to stop the billing.

To maximize the use of each billing cycle and to avoid the overhead of restarting Lambdas, InfiniCache’s Lambda runtime uses a timeout scheme to control how long a Lambda function runs. When a Lambda node is invoked by a chunk request, a timer is triggered to limit the function’s execution time. The timeout is initially set to expire within the first billing cycle.

If no further chunk request arrives within the first billing cycle, the timer expires and returns 2–10 ms (a short time buffer) before the 100 ms window ends. If more than one request can be served within the current billing cycle, the heuristic extends the timeout by one more billing cycle, anticipating more incoming requests.

This clever workaround overcomes two limitations simultaneously: adjusting to the round-up pricing model, and ensuring that parallel requests can be served by the single Lambda instance, both reusing the same memory cache.

Instance sizes

AWS Lambda functions can be provisioned at a memory limit between 128 MB and 3 GB. The allocated CPU cycles are proportional to the provisioned RAM size.

InfiniCache authors find larger instances beneficial. Even though they end up paying more for each invocation, they greatly benefit from improved performance, reduced latency variation, and lack of network contention.

We find that using relatively bigger Lambda functions largely eliminates Lambda co-location. Lambda’s VM hosts have approximately 3 GB memory. As such, if we use Lambda functions with ≥ 1.5GB memory, every VM host is occupied exclusively by a single Lambda function.

Chunking and erasure coding

To serve large files with minimal latency, InfiniCache breaks each file down into several chunks. The proxy stores each chunk on a separate AWS Lambda and requests them in parallel on retrieval. This protocol improves performance by utilizing the aggregated network bandwidth of multiple cloud functions in parallel.

On top of that, InfiniCache uses an approach called erasure coding. Redundant information is introduced into each chunk so that the full file could be recovered from a smaller subset of the pieces. For example, “10+2” encoding breaks each file into 12 chunks, but any 10 chunks are enough to restore the complete file. This redundancy helps fight long-tail latencies: the slowest responses can be ignored, so the stragglers have less effect on the overall latency of the system.

The paper compares several erasure coding schemes (“10+0”, “10+1”, “10+2”, etc.) and finds that 10+1—requiring 10 any chunks out of 11—provides the best trade-off between response latency and computational overhead of encoding.

Predictably, the non-redundant “10+0” encoding suffers from Lambda straggler issues, which outweighs the performance gained by the elimination of the decoding overhead.

Interestingly, breaking down a file into chunks becomes the responsibility of the client library. The encoding is too computation-heavy to be executed in the proxy.

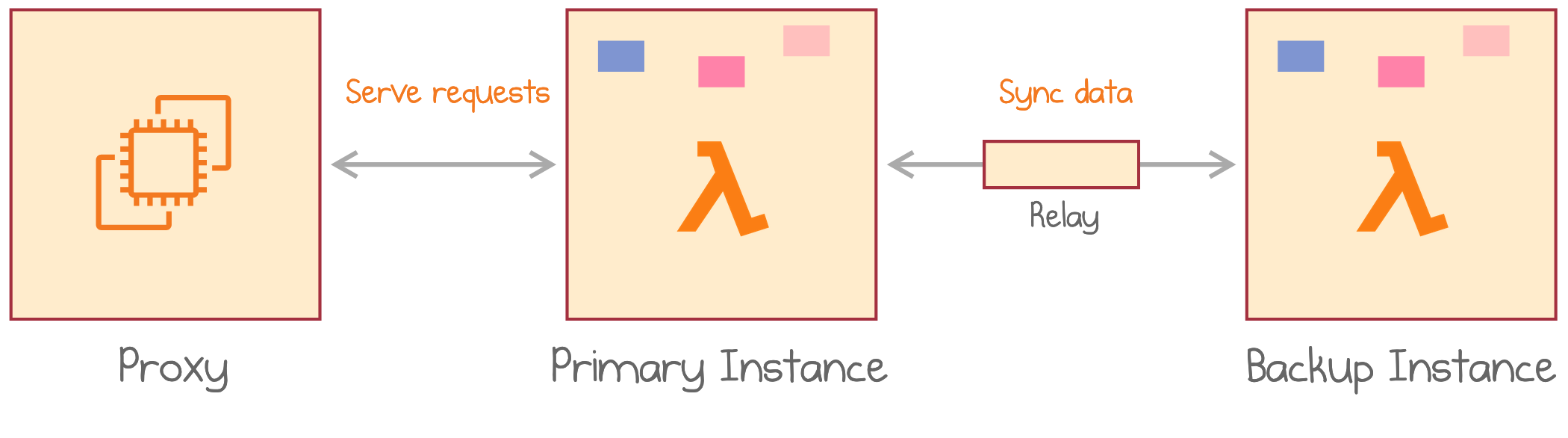

Warm-ups and backup

Amazon can reclaim any inactive instance of an AWS Lambda at any time. It’s not possible to avoid this altogether, but InfiniCache does three things to mitigate the issue and keep the data around for longer:

-

They issue periodic warm-up requests to each Lambda to prolong the instance lifespan;

-

The redundancy of erasure coding helps recover lost chunks of a single object;

-

Each cloud function periodically performs data synchronization with a clone of itself to minimize the chances that a reclaimed function causes a data loss.

The last point is referred to as “backup” and is uniquely elegant, in my opinion. How does one backup an instance of AWS Lambda? They make the Lambda invoke itself! Because such invocation can’t land on the same instance (the instance is busy calling), the second instance of the same Lambda is going to be created. The two instances can now sync the data, which happens over TCP through a relay co-located with the proxy.

AWS Lambda creates the second execution of itself and syncs data between the two executions

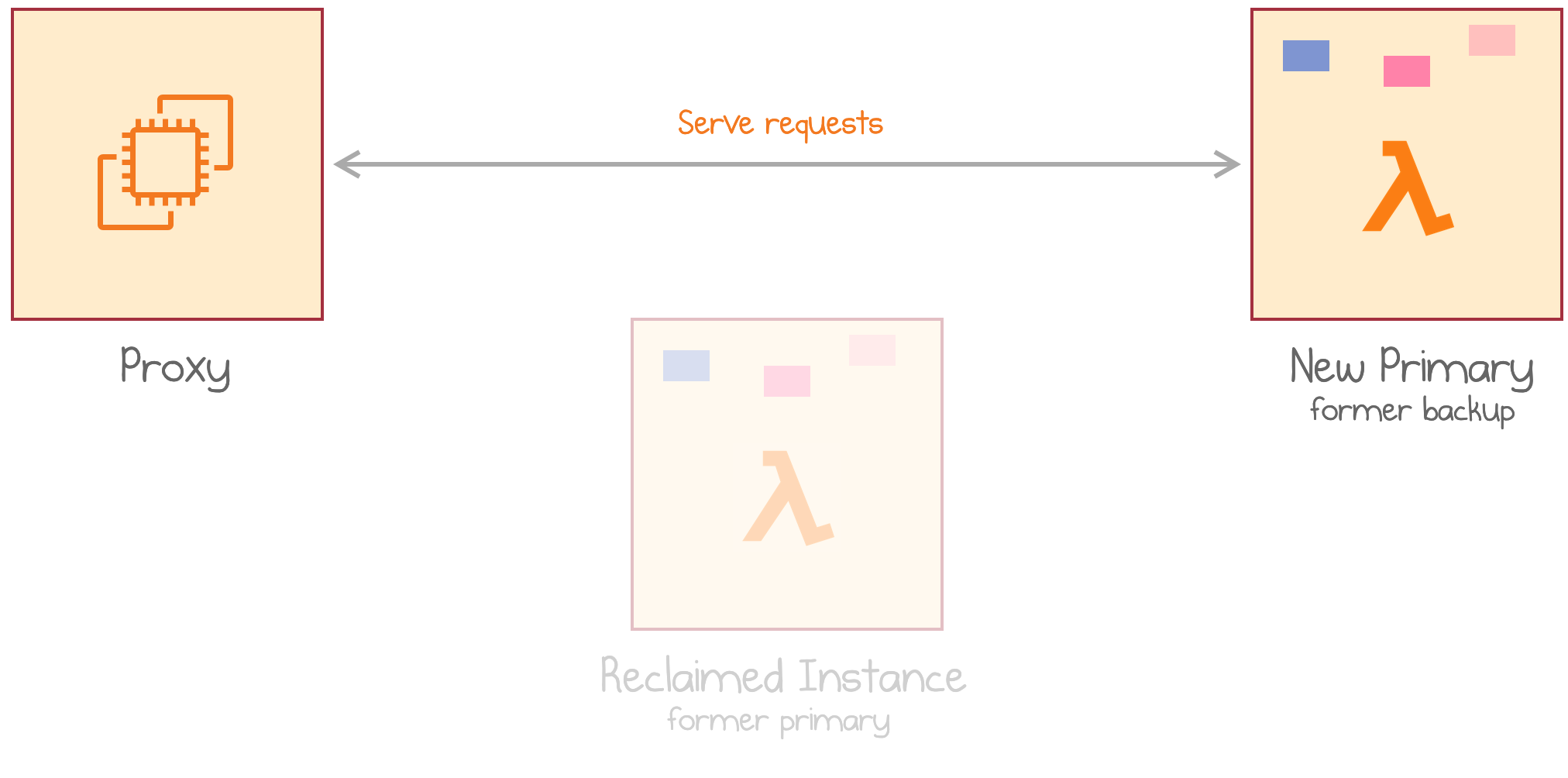

If AWS decides to reclaim the primary instance, the next invocation naturally lands on the secondary instance, which already has the data in memory.

AWS reclaims the primary instance which automatically promotes the secondary instance with hot data

The promoted instance can now start another replication to create a backup of its own.

Both warm-ups and backups largely contribute to the total cost of the solution, but the authors find this cost justified in terms of improved cache hit rates.

III. Practical Evaluation

The authors implemented a prototype of InfiniCache and benchmarked it against several synthetic tests and a real-life workload of a production Docker registry. Below are some key numbers from their real-life workload comparison against an ElastiCache cluster (a Redis service managed by AWS). Mind that the workload was selected to be a good match for InfiniCache properties (large objects with infrequent access).

Cost

InfiniCache is one to two orders of magnitude cheaper than ElastiCache (managed Redis cluster) on some workloads:

By the end of hour 50, ElastiCache costs $518.4, while InfiniCache with all objects costs $20.52. Caching only large objects bigger than 10 MB leads to a cost of $16.51 for InfiniCache. InfiniCache pay-per-use serverless substrate effectively brings down the total cost by 96.8% with a cost effectiveness improvement of 31x. By disabling the backup option, InfiniCache further lowers down the cost to $5.41, which is 96x cheaper than ElastiCache.

However, they find that serverless computing platforms are not cost-effective for small-object caching with frequent access.

The hourly cost increases monotonically with the access rate, and eventually overshoots ElastiCache when the access rate exceeds 312 K requests per hour (86 requests per second).

Another gotcha is that the cost above does not include the price of a proxy: the proxy was co-located with the single client VM. A dedicated proxy running on an EC2 instance would increase the total price considerably.

Performance

Here are the key conclusions based on a production-like test of InfiniCache:

-

Compared to S3, InfiniCache achieves superior performance improvement for large objects: it’s at least 100x for about 60% of all large requests. This trend demonstrates the efficacy of the idea of using a distributed in-memory cache in front of a cloud object store.

-

InfiniCache is particularly good at optimizing latencies for large objects. It is approximately on-par with ElastiCache for objects sizing from 1–100 MB, but InfiniCache achieves consistently lower latencies for objects larger than 100 MB, due to I/O parallelism. However, I suppose chunking could improve the results of ElastiCache too.

-

InfiniCache incurs significant overhead for objects smaller than 1 MB, since fetching an object often requires to invoke Lambda functions, which takes on average 13 ms and is much slower than directly fetching a small object from ElastiCache.

Availability

Hit/miss ratio is an essential metric of any cache. A cache miss is usually a result of an object loss when all the replicas of several chunks are gone.

For the large object workload, a production-like test resulted in the availability of 95.4%. InfiniCache without backups sees a substantially lower availability of just 81.4%.

IV. Future Directions

Can a system like InfiniCache be productized and used for production workloads?

Service provider’s policy changes

InfiniCache uses several clever tricks to exploit the properties of the existing AWS Lambda service as it works today. However, the behavior of Lambda instances is broadly a black box and changes over time. Even small behavior changes may potentially have a massive impact on the properties of InfiniCache-like systems.

Even worse, service providers may change their internal implementations and policies in response to systems like InfiniCache. Ideally, any production system would rely on explicit product features of serverless functions rather than implicitly observed characteristics.

Explicit provisioning

AWS Lambda has recently launched a new feature called provisioned concurrency, that allows pinning warm Lambda functions in memory for a fixed hourly fee. Provisioned Lambdas may still get reclaimed and re-initialized periodically, but the reclamation frequency is low compared to non-provisioned Lambdas.

The pay-per-hour pricing component is quite significant, which brings the cost closer to EC2 VMs' pricing model. Nonetheless, it opens up research opportunities for hybrid serverless-oriented cloud economics with higher predictability.

Internal implementation by a cloud provider

Finally, instead of fighting with third-party implementations of stateful systems on top of dynamic function pools, cloud providers could potentially leverage such techniques themselves. A new cloud service could provide short-term caching for data-intensive applications such as big data analytics.

Having the complete picture, datacenter operators would operate a white-box solution and could use the knowledge to optimize data availability and locality. I look forward to new storage products that can more efficiently utilize ephemeral datacenter resources.

Responses